On Friday, I go mushroom foraging with a stranger from the internet. I do this for 3 reasons:

I’m gay.

I don’t know how to do anything — make friends, go on vacation, flirt — without doing a second thing.

I’m trying to accept that I have moved, and that I need to get to know who and what lives here, in this new place, with its new roads and its new amenities and its new plants and its utter lack of HEBs. (I’m sorry to tell you this, northerners, but a Kowalski’s is no HEB. Can a Kowalski’s keep your electrical grid up and running while your politicians run away to Mexico? I didn’t think so.)

The stranger from the internet and I meet at a park that runs along the Mississippi River. This far north doesn’t experience the raging hot summers my old home did — in fact, we’ve been having a cool, wet spell — so I’m wearing a long sleeve shirt and overalls. (Overalls. In August. This isn’t a brag, it’s terror: how cold is it gonna get up here?!) All the damp and cold are good omens for mushrooms. The stranger from the internet greets me by shaking my hand, a queer contract of sorts, and we start down a trail.

It takes us about 2 feet to spot our first mushroom. A hand-sized fungi fans out from the sandy soil beneath a bunch of jewelweed, its gills a deep autumn yellow.

“Break it open,” says the stranger from the internet.

I pick up the mushroom and snap off a piece of its cap. At the breakage point, milk begins to ooze.

“Lactarius,” confirms the stranger from the internet, beaming.

My first mushroom is a milker.

I’ve lived in a lot of places as an adult, most of them by choice. Whenever I move, I tend to add a bunch of new stuff into the mix: new hobbies, new projects, new ways to get myself out of the house and connect with other people. When I moved to Mexico City, for example, I got really into going to experimental punk shows and getting the shit kicked out of me. When I moved to Providence, RI, I got really into butchery. For one winter in Maine, I got into the habit of driving my ‘93 Jeep Grand Cherokee around the snowy back roads searching for road kill that I could make ink illustrations of later.

Mushrooms make sense as a new hobby of mine. I’ve been curious for a while. Back when I was Bridget,1 I even wrote a horror story about mushrooms turning a couple lesbians into mushrooms that won a prize and eventually made its way into a collection of body horror I published a year and a half ago. Now, I’m finding that mushrooms make an especially thrilling as a hobby for someone whose nervous system is regularly fucked. They aren’t an indoor activity: they require you to be outside, touching things, smelling things, going on walks without any distraction. They require tools: a brush, for gently cleaning off your mushroom, and a special kind of knife, so you don’t damage the mycelium network below the soil as you forage. Mushrooms are, after all, the fruiting bodies of an entire community, and you don’t want to cause harm to that community. That community does a lot of work in often apocalyptic circumstances. Best treat the community with respect, and if you’re going to take a fruiting body, do it sparingly and with gratitude.

Mushrooms also require utter focus, and curiosity. If you’re trying to identify a mushroom, for example, it isn’t enough to Google “yellow mushroom Minnesota.” There are so many data points you need answered before you have anything close to an answer. For instance:

Is it growing on a tree, or out of mulch, or out of bare soil?

Are there a lot in the area, or just one? Is it growing in a cluster? Does it grow in circles or in strips?

Is the cap all one color, or does it kind of change? How does it change?

If you break off a piece of the cap, what happens?

When you break open the stem, is it hollow? Does it peel like string cheese? Does it smell fruity? Earthy?

Does it have gills or ridges or teeth? Do you know the difference?

And after all of that, you still might not know what the mushroom is. Arrogance is a killer. Isn’t that thrilling?

Mushrooms are the subject of some pretty fucking epic lore, especially for the formerly-religious among us. A Christian folktale says that jelly ear — “Auricularia auricula-judae,” from the Latin words for “ear” and “Judas” — grew on the tree where Judas Iscariot hanged himself for betraying Jesus Christ. (That alone deserves its own folk song, it just occurred to me…)2

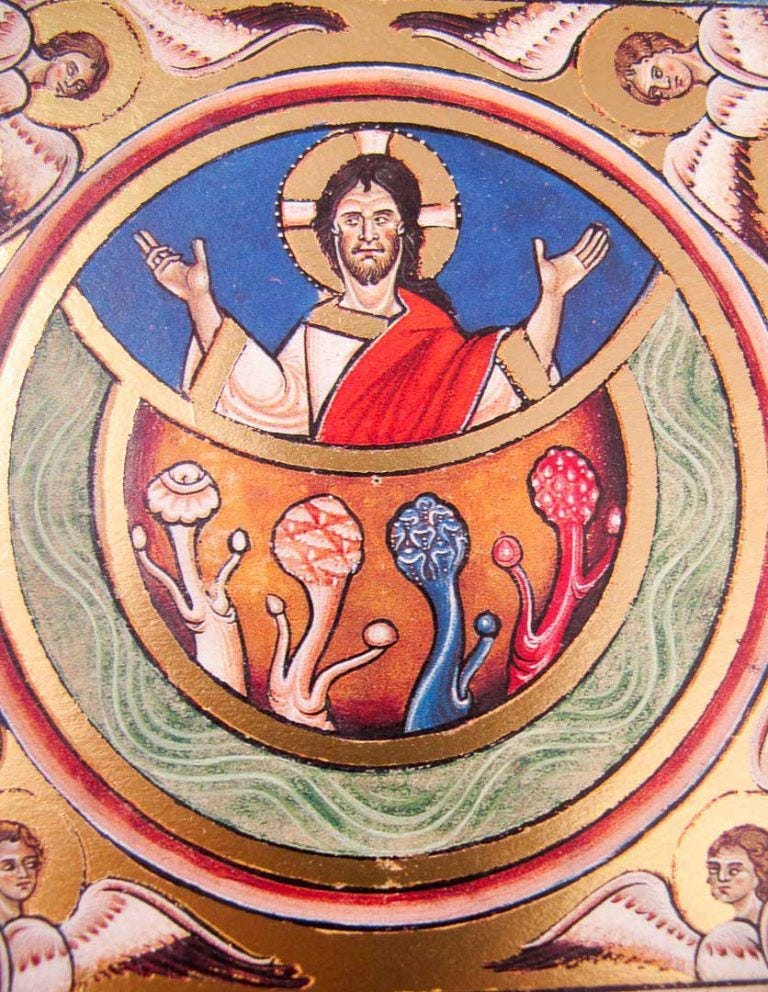

Another wild Christian-mushroom crossover: in 1970, an absolutely unhinged British archaeologist and Dead Sea Scroll scholar named John Marco Allegro wrote a book called The Sacred Mushroom and The Cross. In it, he argues — I feel compellingly, or at least with an interesting outsider passion — that Jesus never existed as a historical figure, but was rather a mythological creation of early Christians who were under the influence of psilocybin.

In fact, Allegro asserts, Jesus was a mushroom Himself: Amanita muscaria, to be exact. You know. Like the emoji. 🍄.

It only takes the stranger from the internet and I twenty minutes of rifling through leaf litter on our hands and knees, gathering a bounty of chanterelles and pheasant backs and hedgehog mushrooms, before we start talking about church camp. The stranger from the internet was a church camp counselor for a while, and led a lot of prayer hikes that sometimes crossed over into square dances. Mostly Lutheran camps, which is common this far north: there are so many Lutheran churches that dot the fields and hillsides, tidy and beautiful in their humble ways. For my part, I’ve been in and out of church camps my whole life: a Lutheran Vacation Bible School every summer, two Encounter retreats in high school, and a silent retreat at a convent in a Louisiana swamp as an adult studying to become a nun.

It makes sense to me that the stranger from the internet and I once went to church camp and are now eager to spend hours outside in the woods, digging around for mushrooms. It makes sense to me, too, that Christianity and other death and fertility cults often include an interest in mushrooms. When you think about it for more than a few seconds, fungi quickly approaches the divine. For example, underground mycelium networks mean that mushrooms are always with us, even when we can’t see them. They’re often a means of communication and service between trees, and they usher in new states of being through decomposition. To find a mushroom you know isn’t really unlike having a vision of Jesus, and I’m not even talking about the psychedelic mushrooms.

Once again, I find: you can take the guy out of the religion, but not the god-shaped hole out of the guy. Something’s gotta fill it. These days, it’s mushrooms.

I don’t know how long this mushroom hobby will last. In any case, winter means the time for mushroom foraging is over, and already the days are growing shorter and cooler up here. For my part, I’m also about to have a busy little fall: I’m playing a couple sets at this year’s Americanafest in Nashville, I’ve been invited as an official artist to showcase at Folk Music Ontario, and I’ll be running around down south with my buddy-fiddler Beth Chrisman as an official artist at this year’s Blackpot Festival down in Lafayette, Louisiana, plus a bunch of shows in a bunch of places in between. (Keep an eye on my Instagram or my Shows page to see where I end up!) Working musicians don’t get a ton of time to rest if we want to make rent, so my days of mushroom foraging will most likely end when August does.

But for now, searching for fungi means learning the ways of oak and maple and birch. It means learning what jewelweed is, and why it often grows next to poison ivy. It means following deer paths, because deer paths like mushrooms, too, and it’s nice to have something in common with the deer.

It means looking. It means listening. It means moving with care. It means believing that I’ll see something somewhere that’s worth finding.

A few nights ago, I got brave and ate a piece of what Little Girlfriend and I determined, after much study, to be a real chanterelle I found on my walk with the stranger from the internet. False chanterelles — also called jack-o’-lanterns — glow in the dark in big clumps on trees and work with fairies to trick you into getting lost. They also make you puke. But real chanterelles grow yellow and solo, right out of the ground, with veiny-looking ridges that run right up to the cap. When you break them open, their stems are white and peel like string cheese, and the meat smells like apricots. They never grow on trees.

It was time to get brave. I fried up a piece, ate it, and waited.

Every fart brought a thrill of terror: had I been wrong, after all? Had the stranger from the internet not known how to tell these mushrooms apart from their doppelgängers? How much puke? How much pain, if I was wrong?

Eating a mushroom you find in the wild, like moving across the country, requires its own leap of faith.

Reader, I didn’t die. Instead, I got to eat my very first chanterelle pasta, cooked in butter and lemon juice with shallots and garlic, and I’ll be damned if I didn’t lick my plate clean and see God in the smears.

My name used to be Bridget. I guess it’s technically my “dead name,” but even with all the dysphoria that came with being Bridget, I don’t think of her as dead, and I don’t mind you knowing that I used to be tucked inside her. These days, Bridget is more like a very lovely but ill-fitting dress I keep folded in a chest at the back of my closet.

As soon as I wrote down the stuff about Judas and jelly ears in Christian folklore I sat down and wrote a folk song about it. I’ll release it later this week for paid subscribers, so if you want in, you better upgrade that subscription, bud!