Below is a list of future careers I envisioned for myself as a child:

A writer

A pony

I wanted to be a pony, specifically, and practiced eating grass in the front yard on all fours until I threw up and realized my stomach shared none of my aspirations

A nun

In my humble, 12-year old opinion, I’d make a great nun. I had the stamina — that is, I knew how to suffer. I knew how to be humiliated. Altar girl, unpopular, weird-looking. I prayed on my hands and knees every night on a small pew in my bedroom until they ached. I gave myself “stigmata” and bruised myself on purpose, to know pain. I read the Bible every night, looked for signs of God in everything. I turned myself into anything anyone wanted me to be, so that they’d feel good about being around me. In my mind, that was how I could serve others. I got good at it.

So often I felt God moving through me. Listening to music in the car gave me that feeling. And when I ran so hard I left my body. And when we sang in Latin at the end of Mass to the statue of the Virgin Mary. And when my best friend rolled over in her sleep and pressed her back against mine. It all gave me the same tingle on my arms, the same light-headed feeling. Ecstasy. Wonder. All the saints described that feeling as the Holy Spirit, so what else could I call it? I could be a nun. I could be an incredible nun. I could garden, and live with only women, and pray all the time, and hurt myself, and feel God, and serve others above myself, and be good.

Later, I realized my mistake. I hadn’t been studying to be a nun: I’d been studying to be a saint.

Also, I was probably gay. Go figure.

Making art about Catholicism is a recent development for me, something that really only took shape in the last 5 years. Now, Catholicism touches everything I make. Digging up bones is a complicated pleasure. Like rubbing a rabbit’s ear you used to keep in your pocket for luck that ended up failing you, or finding a letter from a friend you don’t speak to anymore. Now, working from a Catholic place makes me realize just how much I’ve been denying that landscape was a part of me. I never feel patriotic, and I hate the town where I’m from, but Catholicism is about as close as I’ll ever get to having a homeland. It may be a death cult dressed up in the garbs of personal punishment, but it’s my death cult dressed up in the garbs of personal punishment. And, same as any countryman, I sometimes long to get a glimpse of it again. To remind myself that it happened, to feel relief that I’m out, or even — and this aches the most — to allow myself some comfort in the feeling of familiarity. Estranging myself from my family has made familiarity feel precious, if painful.

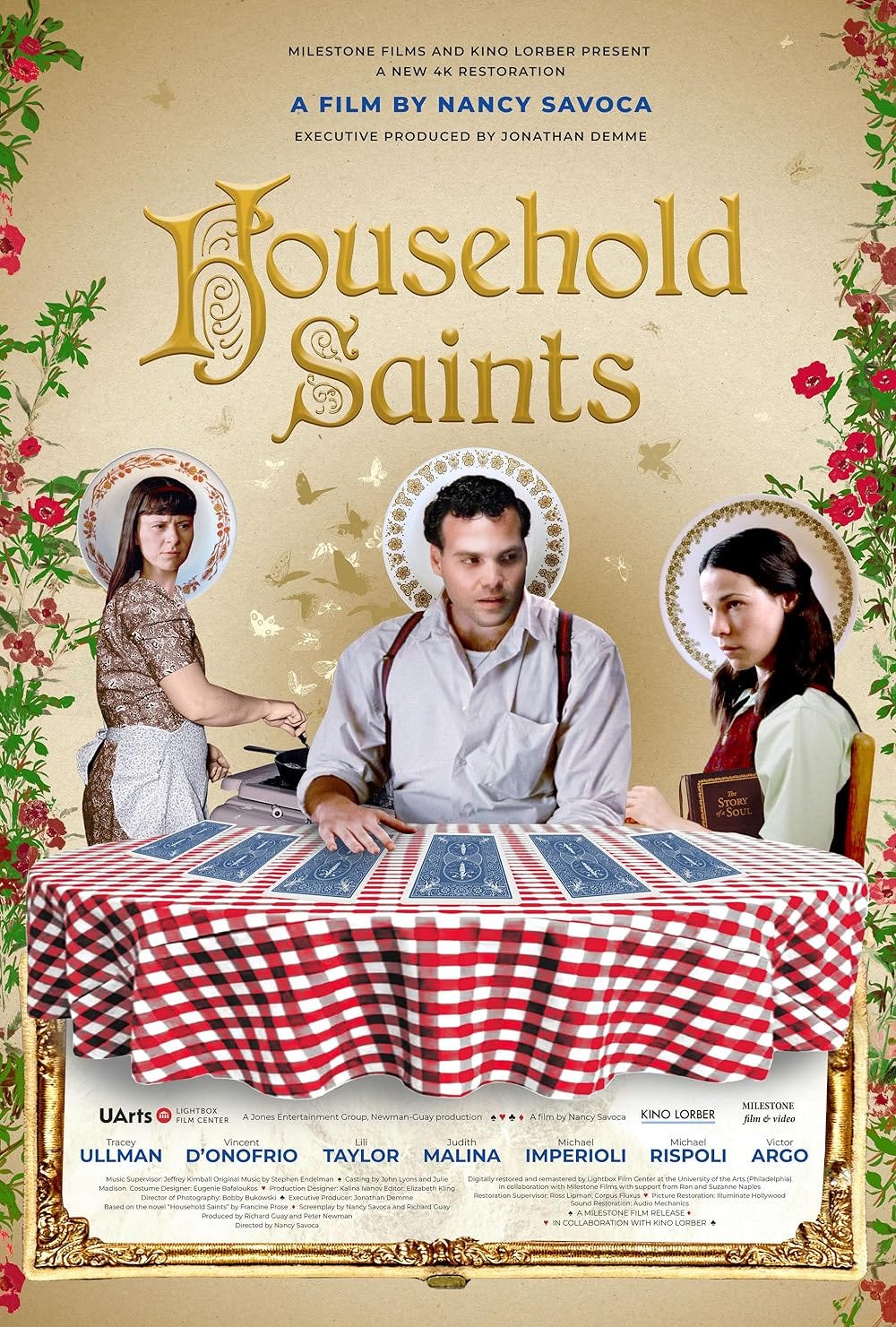

The other night, Asher and I watched Household Saints, a wild, deeply Catholic-Italian movie from 1993 produced by Jonathan Demme (who also directed The Silence of the Lambs and Stop Making Sense, that concert-film about The Talking Heads that got re-released this summer and gave all of us big-time gender feelings). I don’t really know that much about film criticism or theory — that’s Asher’s bag — but I do know a lot about religion, and this is one of the better films about religion out there, in my opinion. It lands somewhere ambiguous: an answer to the question “What makes a saint real?” is less important here than “So what now?”

I AM SO FASCINATED BY THESE QUESTIONS, and by the way the religion of my upbringing seems torn on how to handle them. Household Saints, with its tragic/comic blend of Italian folk magic and Catholic superstition and personal longing and faith, maneuvers between those questions so well. This is a movie worth thinking and writing about as a former Catholic who now makes work about Catholicism. I think this is a movie worth thinking about if you aren’t those things; if, instead, you’re a person living in a time when we are constantly facing a barrage of easy questions that evade harder truths.

Also all Catholic movies are trans. In this essay, I will prove it.

First, the highlights:

The tagline for Household Saints on the poster says, “The Santangelos asked for a miracle. God gave them something slightly more complicated. Their daughter Teresa.” I don’t know who wrote the copy for that, but damn, is that good. That person earned their paycheck that day

The tragicomedy of it all — we here at Creekbed Carter Industries live laugh love for a laugh/cry/laugh sandwich

The sausage. THE AMOUNT OF SAUSAGE JOKES. There is so much sausage in this movie

That part where someone might give birth to a chicken and the shadow of wings flash across the window. Incredible, unforgettable, wowee

Teresa’s vision of Jesus and all that gingham, I swear to God there has never been a weirder, more quotidian depiction of a vision of Jesus in all of film history. Every Gender and Sexuality Film 101 course should teach this scene

The extremely Catholic framing devices

That epic opening scene of the 4 men playing pinochle shrouded in the steam from the very tomb-like ice box. Truly just such a fable of a moment, utterly memorable

Household Saints and Catholic narrative forms

To describe the plot of this movie, I have to first define Catholic forms of narrative. Catholicism so often deals in forms-within-a-form. Relics, for example, are displayed within ornate containers called reliquaries that evoke the life and death of their namesaint. Not only do you see the sacred body-object, you also see the story of that body-object when it was still a part of its pious host:

This isn’t just a Catholic thing — many organized religions center texts that involve figures telling a parable about a parable about a thing that happened. I remember pieces of the Q’uran feeling this way, for example, and I feel like I find a similar narrative form when I encounter Jewish narratives. (Y’all ever seen A Serious Man? A real home run for the story-within-a-story form.) It’s a narrative conceit I love a lot, ancient and somehow always new. I’m writing a song right now that’s trying to use this framing device of a story-within-a-story, a truth-inside-a-container, so I’m particularly invested in this shit, and I personally always think it’s interesting when songwriters make allusions to cultural influences in their work in ways that reach beyond their lyrics. Kaia Kater’s absolute legend of an album, Nine Pin, is a great example of form alluding to a bigger project.

Have I lost you yet or are you into this?

Whatever, I’ll keep going and hope this isn’t too boring to you. Special interests are like that sometimes.

Household Saints begins, then, as a story within a story. An Italian-American family sits under the big blooms of summer at a wooden picnic table, sharing a feast and gossiping in a blend of English and Italian. One gossip leads to another, and soon they’re telling the tale of the Falconettis and the Santangelos and their strange, divine daughter, Teresa. You’ll forget that the movie you’re watching is basically a story being told around a dinner table until you get to the very last scene, when you return to the family and the picnic and the crying babies and the big leaves of summer. I love that circular form. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Big-time pagan influences out here — which is, of course, also a deeply Catholic move, to “borrow” pagan shapes of ritual and storytelling.

The first third of this movie is funny and surreal and full of folk religion and side plots. Here’s one: Carmela Santangelo, who bitches about her son’s marriage choice all the time to her dead husband Enzo, threatens her son’s new wife with old wives’ tales. Like: “If you watch a chicken get butchered while you’re pregnant, you’ll give birth to a chicken.”

“I felt it moving,” says Tracey Ullman in awe after watching a chicken get butchered while pregnant. She rubs her belly. “I felt its wings.”

For 10 minutes, you really believe that woman’s gonna give birth to a chicken. That’s the kind of movie you think you’re in. Instead, it’s a stillbirth, so sad and ordinary it actually hurts. It’s good that Teresa’s conception is accompanied by flowers suddenly blooming out of nowhere. Just like that, the narrative pendulum swings from funny to devastating to hopeful, back and forth, over and over.

All Catholic movies are trans movies

Look, I know I’m trans, and my tendency is to see transness in everything — that’s that divinity in me, y’allllll — but sometimes I think that being trans and being a bride of Christ are shot-for-shot the same experience.

In Household Saints, Teresa is an outsider from the start. Her father is a Man: he’s strong, charming, sells sausage, wins his wife in a drunk Pinochle game, knows how to provide for his family, etc etc etc. Her mother is less certainly a Woman — she’s not very good at cooking, not very knowledgable in old world wisdom, seems not to understand very much about flirting or femininity — but eventually she knows to paint the walls pastel and get the right fashionable haircuts and do the things a woman-turned-wife does. Teresa seems Other in obvious ways that go beyond her long, unfashionable hair and her long, unfashionable skirts. Everyone, from her classmates to the adults who buy sausage from her father, can tell there’s something off about her, and that’s in large part a reaction to her very extreme devotion to God. (Trannnnns.) Her desire to be a nun, which extends beyond even her normal Italian god-fearing parents’ comprehension, takes her all the way to fasting, obsessively cleaning as small acts of service, and weeping on her bed as she begs for God’s attention. (Gayyyyyy.) Teresa longs for her body to be useful to God by performing small, daily acts well. Laundry, dishes, household chores: this is how she shows God she loves him, and eventually sex also falls into this category. For her, sex is less about desire and more about finding God, and that, my friends, is a deeply trans way of having sex, let me tell you.

My favorite scene of the whole movie is a manifestation of this desire, when Teresa has a vision of Jesus as she’s ironing her boyfriend’s laundry. This Jesus doesn’t look very real — he’s wearing a garment that looks like a high school theater class dyed it in a bathtub, and he’s very white, and sort of silly — but this surrealist, giggly, capital-I Idea of Jesus is exactly what Teresa has been hoping to get a glimpse of. It’s all very parable of Martha and Mary, where Martha works hard to clean her home for Jesus while Mary washes his feet with her precious body oil. Teresa pulls a Martha and refuses to stop ironing the shirt, so desperate to prove that she loves Jesus through servicing her boyfriend. In response, Jesus fills the room with shirts just like the one she’s ironing, and both of them laugh and laugh at the marvel of all that gingham:

When her boyfriend returns, he can’t see the loaves and fishes she has manifested through her faith. All he can see is his crazy girlfriend. But Teresa is ecstatic, boyfriend be damned, so we don’t take his doubt seriously, either.

When she dies in a convent at last, stigmata in her palms and the garden bursting into full-bloom outside her window in a full circle reference to her conception, there’s sorrow there for her demise, but also joy: she’s finally accomplished the form she’s been longing for this whole time. In her case, that form is beyond-body, beyond-gender, beyond-societal expectation: it’s divine, and otherwordly, and of-God. Show me a more trans ending.

Faith is longing with a hopeful edge

It really burns my grits that the American alt-right has so successfully reduced transness in the public sphere of consideration to such basic shit as “transness is hormones” and “transness is surgeries” and “transness hates body” and “transness wants to pass.” If I really consider my transness, formed with deep consideration over decades, then sure, there’s body stuff involved, but in no way does my transness orbit ideas of what my body should or shouldn’t be. (And mostly the body stuff is a societal issue anyway, if I’m being honest. Who says boys don’t have tits? Who says I’m only one thing? Honk shoo mimimi, man.) To me, my transness has a direct correlation with a feeling that has more to do with ironing clothing for unhoused people at the homeless shelter I worked at as a prospective nun than it does with getting surgeries. Transness is a way to understand my own body, sure, but it’s also a way to understand how to relate to others, how to be in solidarity with all, how to love in a way that is not predicated upon ownership or scarcity; it’s a way to try to be a person that cannot be governed, that is not limited to either/or, in a shape of time that is not linear. That’s the great joy of transness for me, and as I understand it, that’s the same joy, the same ecstasy, that my favorite saints write about and speak to.

Sometimes I think faith is longing with a hopeful edge, and despair is longing with a realistic one. Teresa and I shared the same kind of faith: we knew, as children, that we could build a life for ourselves beyond what people told us was possible, and it took trans(trans)cending our expected forms as adults to find it. And, in that same turn, we share the same kind of despair: that realism does, on occasion, win out, must win out, in order for the wheels of capitalism and society to keep on turning. Her uncle, who so loved the opera, for all his problematic ways, dies a sad and lonely death with desires unfulfilled. Her parents do their best to settle for what they can and build the rest. A letter from God that children on the news claim to receive from St Therese and hand to the Pope goes unread, unfulfilled, and so no one can know if it was all a hoax or if it was real.

But isn’t that how it goes, says the family at the wooden picnic table, sharing their meal. Is it God that’s cruel, or the old wives’ tales that are true? Or did you tell it right? I don’t know, finish your food, it’s just a story, the sauce is getting cold.

This article is wondrous and I stopped reading as the movie description started bc I realized I really wanna watch it. 😤 I will return upon further research 🧐